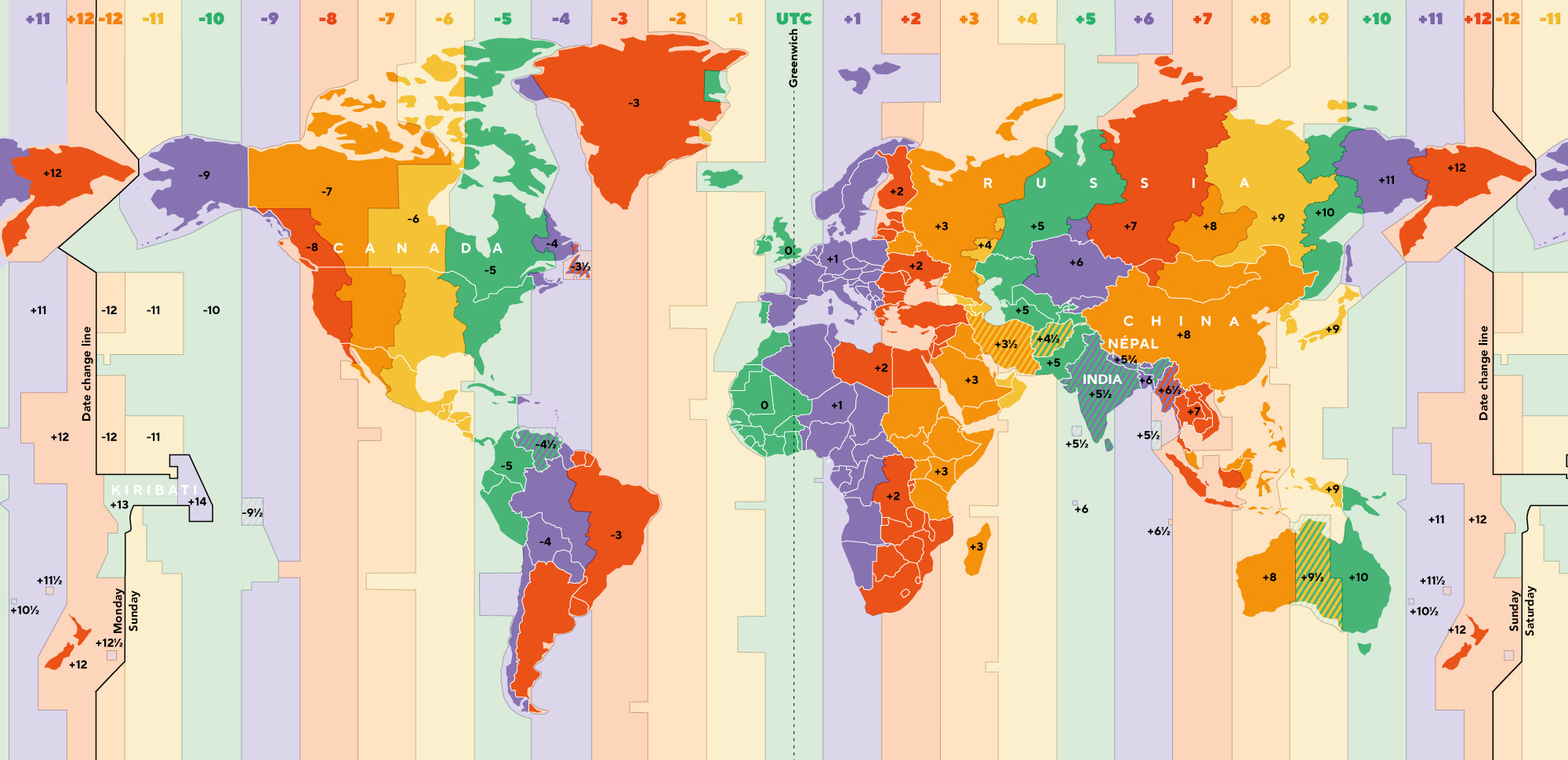

At first glance, the world map of time zones appears to be a logical grid, dividing the globe into 24 orderly time zones. However, as cartography experts, we know that every line drawn on a map hides a story. From the date line being moved to unite a nation to countries setting their time to make a geopolitical statement, time is far from obeying only the sun. Discover how the cartography of time zones reveals the ambitions, conflicts, and whims of human history.

The notion of time zones may seem self-evident today: a world divided into equal slices of time, with each country setting its clocks according to its position relative to the sun. Yet, this organization of time is a relatively recent invention, born of technical necessity, shaped by political choices, and sometimes, marked by absurdity.

Until the 19th century, each city or region used its own “local solar time,” based on the sun's position at noon. Thus, noon in Paris was not the same as in Lyon or London. This posed no problem as long as travel remained slow. But with the rise of railways and telegraphs, this desynchronization became unmanageable.

In 1884, at the International Meridian Conference in Washington, delegates from 25 countries adopted a global reference system: the Greenwich Meridian (in London) would be the zero point of universal time, initially defined as Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) and replaced in 1960 by Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The globe was then divided into 24 time zones, each 15° of longitude in width, representing one hour per slice. The goal was to enable coherent global synchronization. In theory, it worked perfectly. However, in real-world implementation, each state adapted the system to its own circumstances: some modified the delineation of their time zone, others added half-hours or quarter-hours, and some countries even decided to operate with a single time zone for their entire territory, regardless of its vastness.

Even before looking at the clock, one must bear in mind that time is not a natural or universal given: it is a convention agreed to by human societies. And sometimes, these decisions have led to situations far removed from geographical logic.

Daylight Saving Time: Why Do We Change the Hour?

The change between standard time (winter) and daylight saving time (summer) was introduced in several countries to make better use of natural light and reduce energy consumption. In practice, this means that in the spring, clocks are moved forward one hour (we “lose” an hour of sleep), which shifts human activities to times when it is still light out. In the fall, we move back one hour (we “gain” an hour of sleep) to return to “standard” time. The idea is simple: to align hours of activity with hours of sunlight, especially in regions where the days get much longer in summer.

However, this system is not without controversy. Several studies have questioned its real benefits for energy consumption and highlighted its negative effects on health (sleep disturbances, biological desynchronization). Some countries, such as Russia and Iceland, have abandoned it, while others, including the member states of the European Union, are still debating its possible elimination. In the meantime, twice a year, hundreds of millions of people continue to adjust their clocks to follow a ritual... that seems increasingly contested.

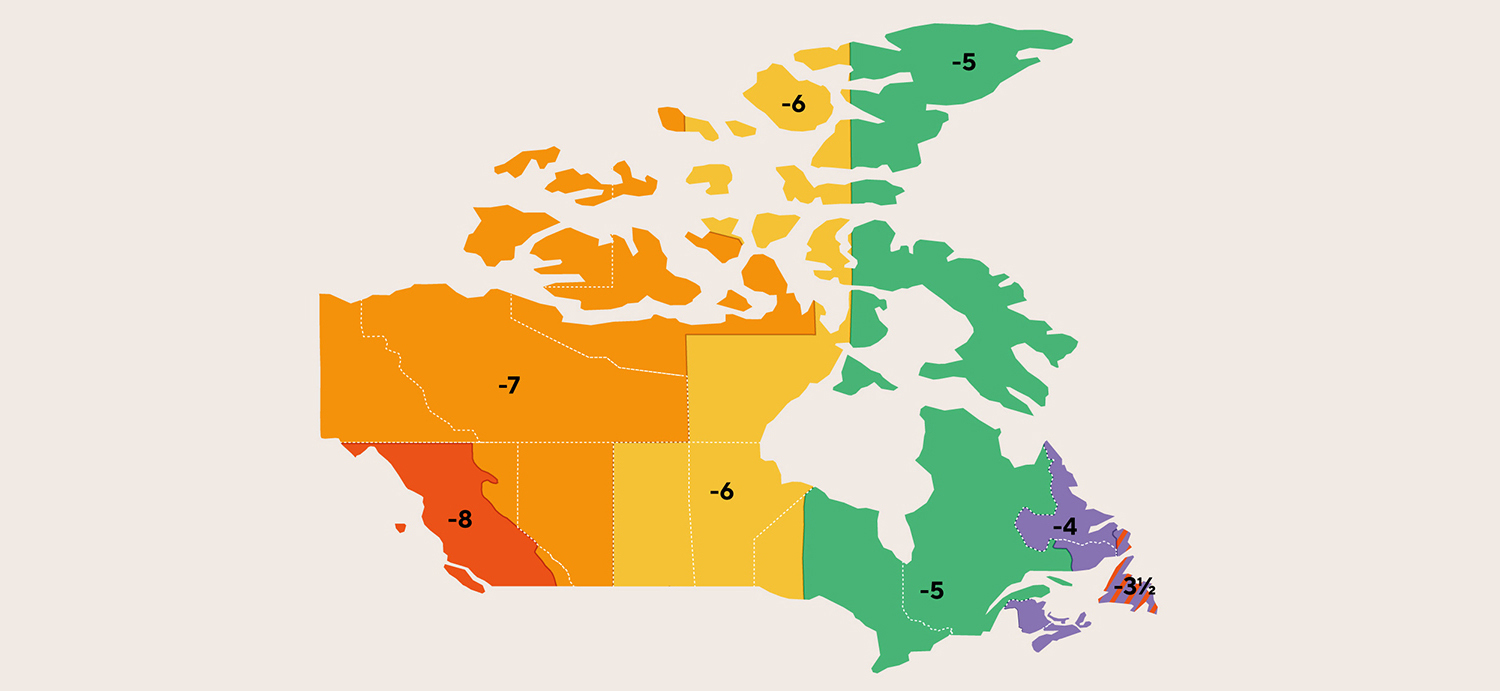

Canada: Measured Diversity... Except in Newfoundland

Canada spans six main time zones, from UTC−3:30 to UTC−8, and offers a fine example of balance between geographical logic and federal organization. Quebec primarily follows Eastern Standard Time (UTC−5), a zone it shares with Ontario and parts of Nunavut. The Magdalen Islands, although located east of the continent and close to the Atlantic time zone, remain aligned with Quebec's official time, illustrating the priority given to administrative coherence over natural geography.

But one province stands apart: Newfoundland, which has maintained a unique 30-minute offset (UTC−3:30) since joining the Confederation in 1949. This half-hour, inherited from its British colonial past, remains in effect today, creating an exception that forces all time management systems in the country to account for an additional variable. It reflects the attachment of Newfoundlanders to their history and their regional distinctiveness. In Canada, even time respects the principle of asymmetrical federalism.

Nepal: National Affirmation, Down to the Minute

Nepal is one of the few countries in the world to have chosen a time zone with a 45-minute offset. Officially, the country sits at UTC+5:45, which may seem trivial, yet is anything but random. This choice reflects a desire for temporal independence from its powerful neighbour, India, which sits at UTC+5:30. By adopting a symbolic 15-minute difference, Nepal subtly marks its cultural and political distinction. This time zone is based on the meridian of Gaurishankar (86°20′E), a sacred mountain located east of Kathmandu. This decision, made in 1986, makes Nepal a unique case in the world, one where the definition of time serves as an expression of identity as much as a practical tool. For travellers, this specificity may seem confusing, but for Nepalis, it is a quiet affirmation of sovereignty.

China: Unity at All Costs

China stretches nearly 5,000 km from east to west, the equivalent of five standard time zones. Yet in 1949, the country chose to operate on a single time zone: UTC+8, which is aligned with Beijing Time. This decision, imposed after the Communist Revolution, aimed to unify the country around a central reference point and strengthen the capital's power. The result: a solar discrepancy that is at times extreme. In the west of the country, in the Xinjiang region, this differential becomes particularly visible. For example, in Kashgar, in the middle of winter, the sun does not rise before 10:15 a.m. Beijing time, while at the same hour in Shanghai, it has already been light for more than two hours. To adapt to this offset rhythm, part of the local population, especially the Uyghur communities, uses an “unofficial local time,” two hours behind the national time, to better align work or prayer schedules with daylight. This contrast between political uniformity and geographical diversity makes China an emblematic case where time becomes an instrument of authority rather than a reflection of reality.

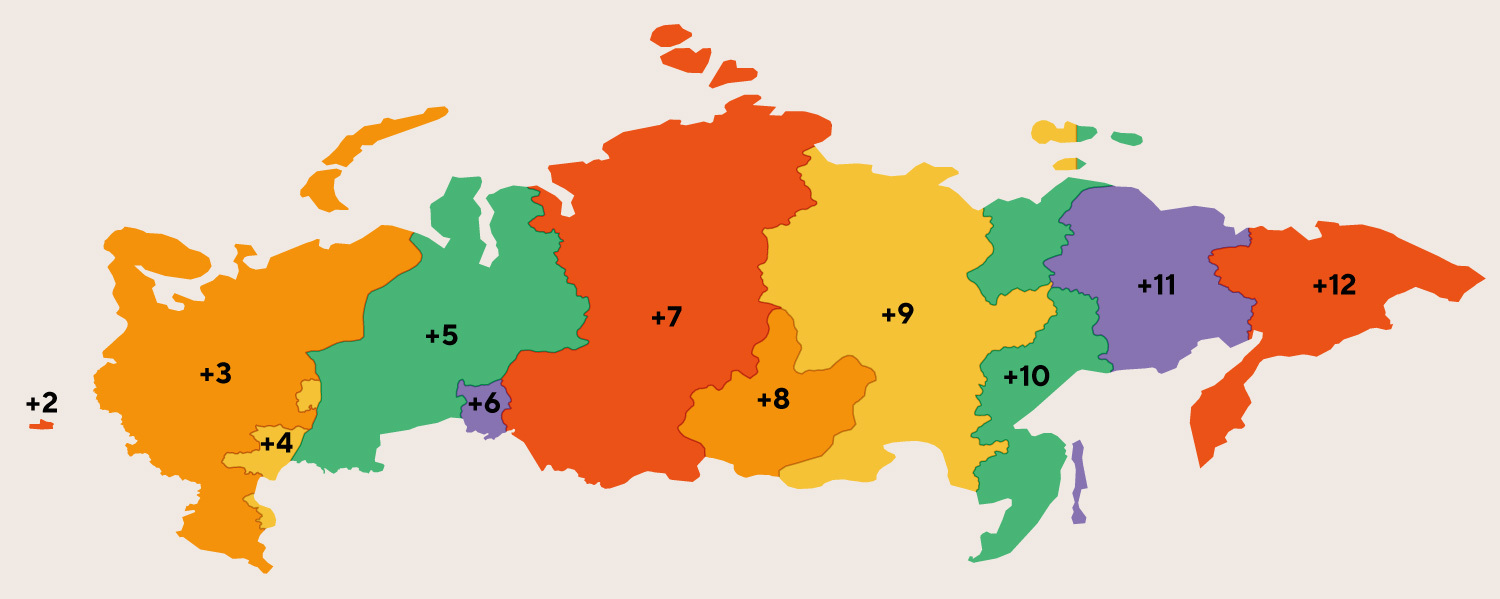

Russia, Stretched Across 11 Hours

With its 11 official time zones, Russia holds the world record. The country extends over 9,000 km from west to east, crossing a temporal range from UTC+2 to UTC+12. This diversity reflects the geographical reality of a gigantic territory, but it has also posed considerable challenges for governance, transportation, and communication. In 2011, the Russian government attempted to simplify this system by reducing the number of zones to 9, but the decision was poorly received by the regions concerned and partially reversed in 2014. Today, Russia is an open-air temporal laboratory, where one can take a train at 3 p.m. in Moscow and arrive at one’s destination at 7 a.m. the following morning without ever leaving the country. This complex system, sometimes restrictive, is nonetheless accepted with pragmatism by Russians, who have long lived by the clock of extreme geography.

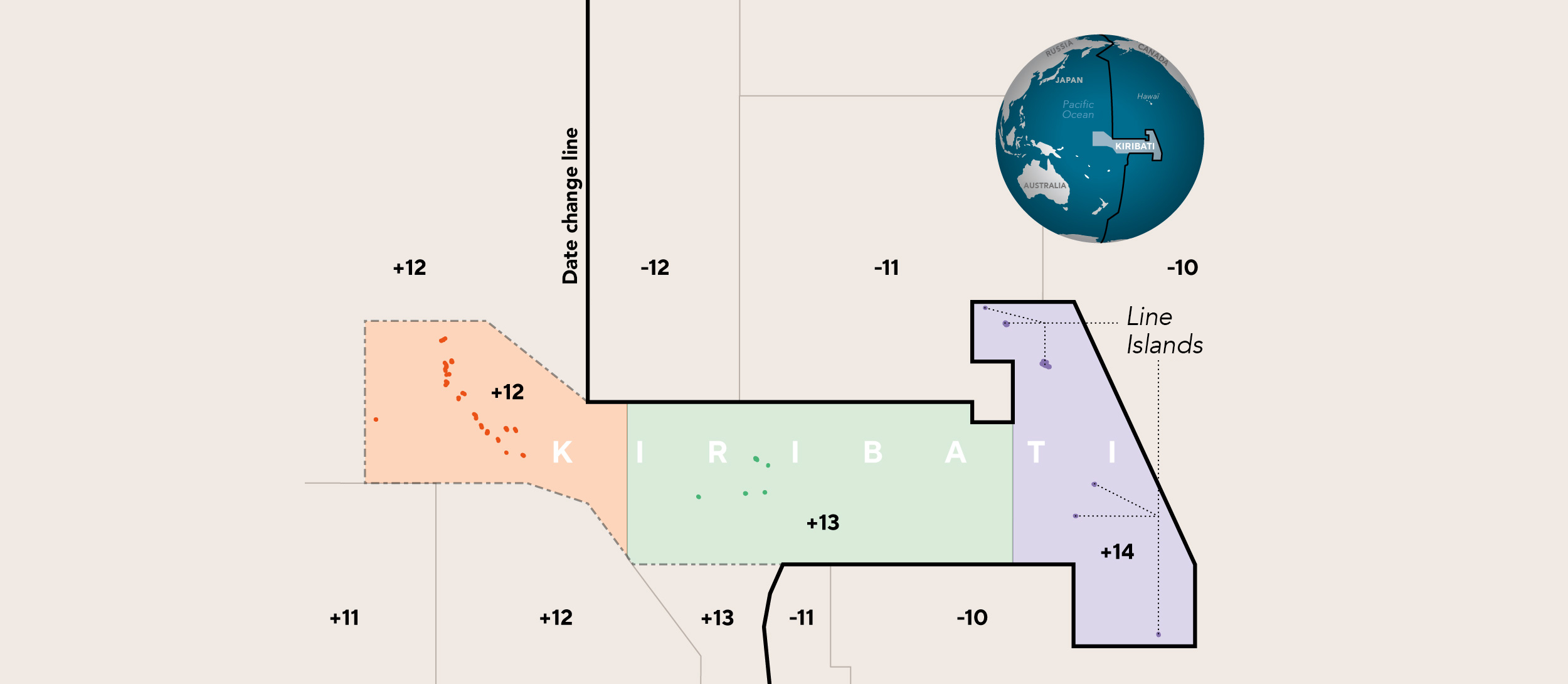

Kiribati: When the Day Changes to Stay United

Kiribati, a small island state in the Pacific, made a historic decision in 1995 that altered the time zone map: it shifted the International Date Line eastward, so that its entire territory, spread longitudinally across several thousand kilometres, would fall within the same calendar day. Before this change, the country's eastern islands (like the Line Islands) technically lived one day behind the rest of the country. This situation made administration, communications, and even national celebrations very complex. By changing its position on the map of time, Kiribati became the first country to enter the new millennium in 2000, which also served as a symbolic and tourist attraction. Today, some of Kiribati's islands live at UTC+14, a time zone that exists almost nowhere else. This case is a striking example of where the geopolitics of time serve to strengthen national unity.

France and Spain: Living on Berlin Time

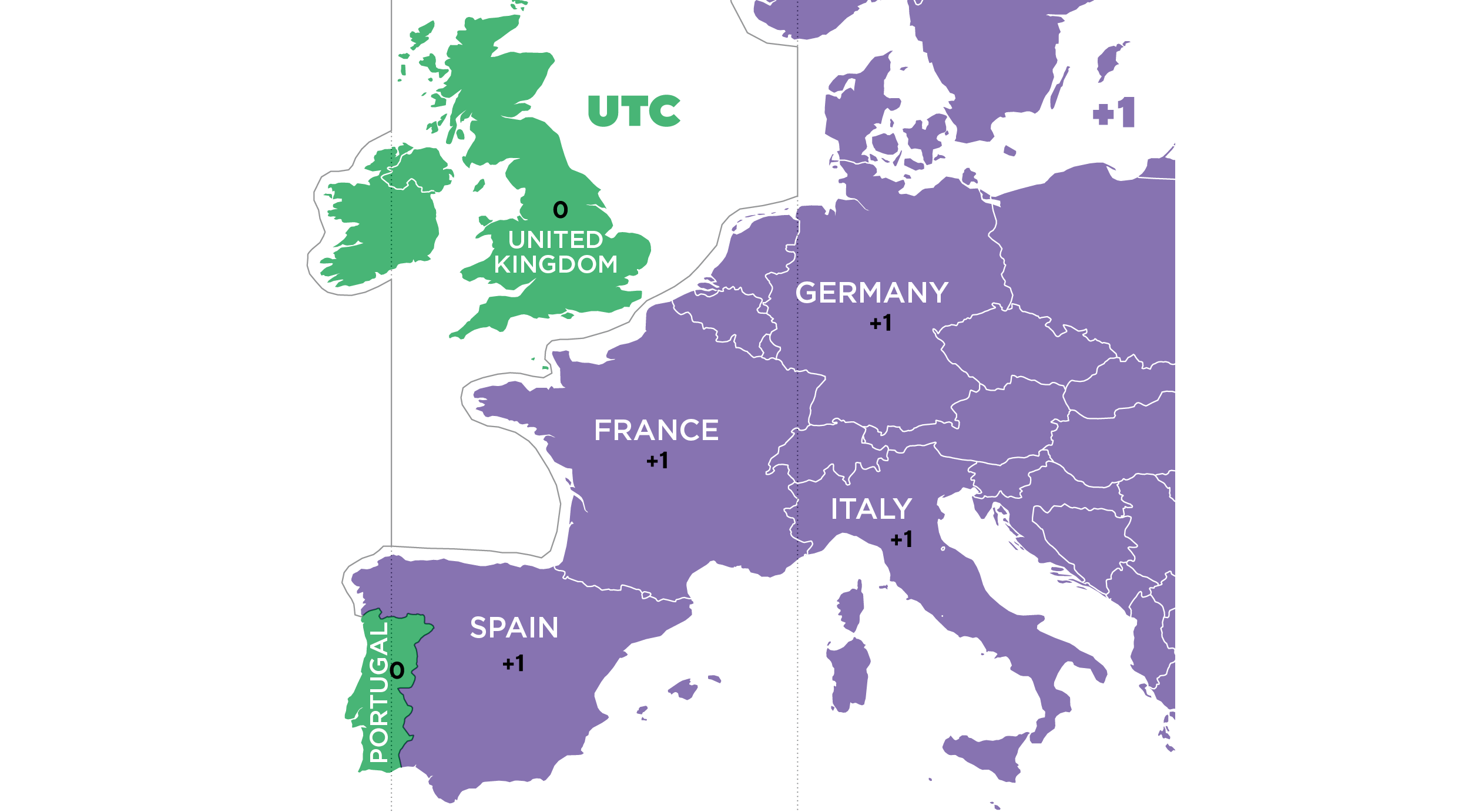

France and Spain share an often overlooked temporal peculiarity: they reside in a time zone that does not align with their natural geographical position. Located to the west of, or near, the Greenwich Meridian, they should logically be at UTC+0, like the United Kingdom or Portugal. Yet, both countries have operated on UTC +1 for several decades, known as “Central European Time,” and UTC+2 in the summer. This discrepancy dates to World War II, when France aligned with German forces under occupation, and Franco's Spain did the same in 1940 out of political solidarity with Nazi Germany. Since then, this choice has never been officially questioned. The result: the sun rises and sets much later than it should. This offset affects life rhythms, sleep patterns, and social organization. Several experts and commissions have suggested a return to natural solar time, but cultural and political inertia remains strong. Living on Berlin time while watching the sun set at 10:30 p.m. in summer: it is one of the most enduring oddities of time in Western Europe.

A Geography of Time, Between Logic and Identity

Timekeeping is not just about the position of the sun, but the history of people. When governments want to mark their distinctiveness, they do so down to the minute. These odd time zones are as so many nods to geopolitics, culture and, often, our humanity.

As you see, the time zone map is much more than a simple geographical grid; it is a mosaic of histories, politics, and cultural identities. This geography of time reminds us that every map is a narrative. Whether you need to visualize a transport network, guide travellers, or illustrate data for a textbook, our expertise is to transform your world into a clear, precise, and captivating map.

Your project also has a story to tell. Contact us to discuss your needs and bring your cartography projects to life!

Sources and references:

Time and Date, Tag Heuer Magazine, WorldTimeServer, National Institute of Standards and Technology, The Economist, BBC News, CNRC.